There are few things in this world that brings feelings of awe and wonder more than a rocket launch. Watching a literal tower of steel slowly lift off from the ground with unspeakable power reminds us of what humanity can achieve despite our flaws, disagreements, and differences, and for the briefest of moments these magnificent spectacles are capable of bringing us all together regardless of race, creed, and religion.

The nation was in love with the Saturn V in the 1960s and 70s as it successfully sent 24 men to the Moon with 12 of them walking on its surface. From the 1980s to the 2000s, the Space Shuttle captivated our hearts and imaginations. But after the Space Shuttle retired in 2011, there were no rocket launches that really grabbed us until SpaceX started launching stuff into orbit and especially when they started landing their own rockets on ocean barges or landing pads.

The real showstopper has been watching SpaceX launch people back into space from American soil, as the private space company has made seven crewed launches into orbit using their Crew Dragon spacecraft, the most recent being Crew-4 to the International Space Station. To go with their crewed missions, SpaceX also frequently launches their Starlink satellites into orbit, along with military payloads, as well. Overall, SpaceX launched 31 rockets into orbit in 2021, and has already reached 26 launches for 2022, which is on pace to absolutely shatter last year’s mark. The pioneering company is also preparing to launch its Starship prototype sometime in the future, which they hope to eventually bring people to Mars.

With other private companies making their mark on the space industry, to include United Launch Alliance, Astra, and Rocket Lab, it’s safe to say watching rocket launches has become almost routine, and the number of launches is only going to keep going up (pun intended). However, as fantastic as these launches are, there’s still a cost to the environment.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) suggests a 10-fold increase in hydrocarbon fueled launches, which is plausible within the next two decades based on recent trends in space traffic growth, would damage the ozone layer, and change atmospheric circulation patterns.

“We need to learn more about the potential impact of hydrocarbon-burning engines on the stratosphere and on the climate at the surface of the Earth,” said lead author Christopher Maloney, a Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) research scientist working in NOAA’s Chemical Sciences Laboratory. “With further research, we should be able to better understand the relative impacts of different rocket types on climate and ozone.”

Launch rates have more than tripled in recent decades, Maloney said, and accelerated growth is anticipated in the coming decades. Rockets are the only direct source of human-produced aerosol pollution above the troposphere, the lowest region of the atmosphere, which extends to a height of about 4 to 6 miles above the Earth’s surface.

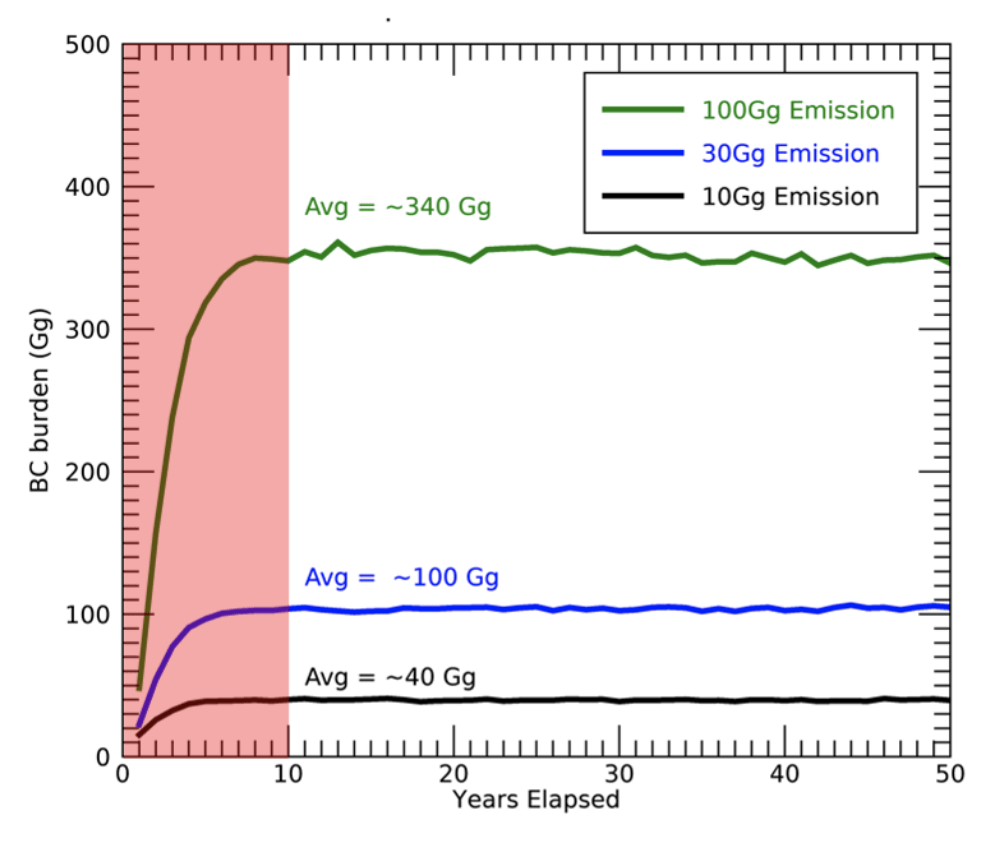

The research team used a climate model to simulate the impact of approximately 10,000 metric tons of soot pollution injected into the stratosphere over the northern hemisphere every year for 50 years. Currently, an estimated 1,000 tons of rocket soot exhaust are emitted annually. The researchers caution that the exact amounts of soot emitted by the different hydrocarbon fueled engines used around the globe are poorly understood. The researchers found that this level of activity would increase annual temperatures in the stratosphere by 0.5 – 2° Celsius (or approximately 1-4°Farenheit), which would change global circulation patterns by slowing the subtropical jet streams as much as 3.5% and weakening the stratospheric overturning circulation.

Stratospheric ozone is strongly influenced by temperature and atmospheric circulation, noted co-author Robert Portmann, a research physicist with the Chemical Sciences Laboratory, so it was no surprise to the research team that the model found changes in stratospheric temperatures and winds also caused changes in the abundance of ozone. The scientists found ozone reductions occurred poleward of 30 degrees North, or roughly the latitude of Houston, in nearly all months of the year. The maximum reduction of 4% occurred at the North Pole in June. All other locations north of 30° N experienced at least some reduced ozone throughout the year. This spatial pattern of ozone loss directly coincides with the modeled distribution of black carbon and the warming associated with it, Maloney said.

“The bottom line is projected increases in rocket launches could expose people in the Northern Hemisphere to increased harmful UV radiation,” Maloney said.

This new research builds upon a previous study led by co-author Martin Ross, a scientist with The Aerospace Corporation. While the new research describes the influence that soot in rocket exhaust has on the climate and composition of the stratosphere, the scientists said it represents an initial step in understanding the spectrum of impacts on the stratosphere from increased space flight.

The New Space Age

Along with SpaceX and the aforementioned private companies launching at a more frequent pace, NASA is planning on sending humans back to the Moon within the next few years using its Space Launch System, China is currently building its own space station in Earth orbit, and India is on a quest to launch their own crewed mission into orbit for seven days in 2022 or 2023. The New Space Age is up and running, but there still might be a toll taken on the Earth for all this activity.

What new research will we unveil about how rocket launches affect the Earth? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!

Press Release: NOAA Research News

Sources: Ars Technica, CNN, Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, Geophysical Research Letters, NASA, Space.com, Financial Express

The post More Rocket Launches Could Damage the Ozone Layer appeared first on Universe Today.

No comments:

Post a Comment