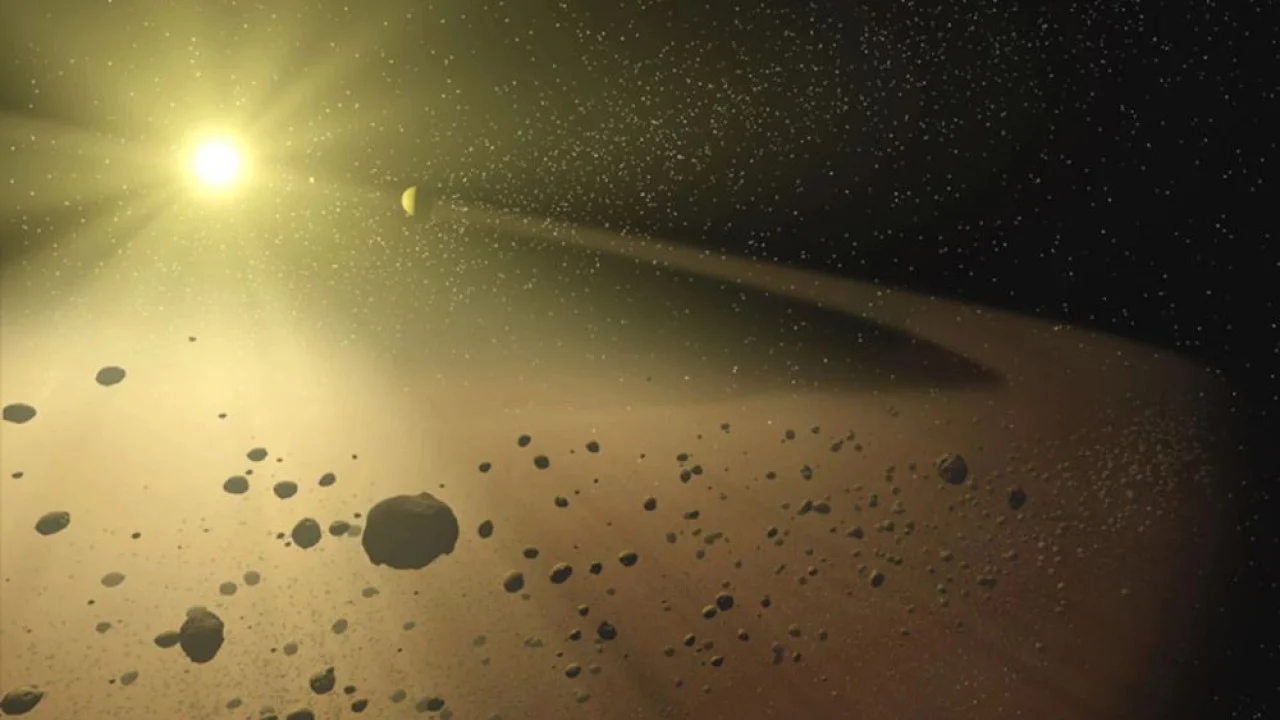

Astronomers suspect that Europa has cryovolcanoes, regions where briny water could erupt through Europa's ice shell, throwing water—and hopefully organic molecules—into space. NASA's Europa Clipper and ESA's JUICE mission are on their way and will be able to scan the surface of the icy moon for signs of cryovolcanism. What should they be looking for? Pockets of brine just below the surface could be active for 60,000 years and should be warmer than their surroundings.