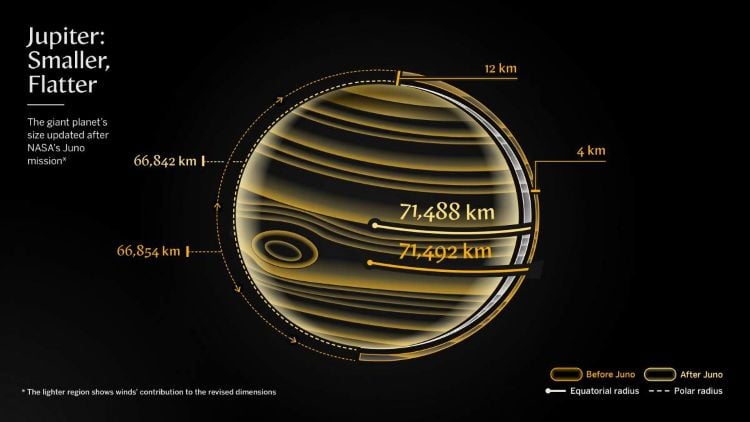

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system and has proudly boasted about this since time immemorial, with its scientific confirmation occurring by Galileo Galilei in 1610. It was later found that Jupiter has a bulging equator caused by its rapid rotation, turbulent atmosphere, and complex interior mechanisms despite its massive size, and scientists have even measured its “waistline” down to a tenth of a kilometer. Now, imagine being the largest planet in the solar system and you’re told you’re not as big as you thought. Where probably most humans would be thrilled to find this out, how do you respond if you’re Jupiter?