![]()

A severe accident at the Baikonur Cosmodrome involving a wrecked maintenance cabin has indefinitely delayed Russia's ability to launch crewed missions and payloads to the International Space Station (ISS).

![]()

A severe accident at the Baikonur Cosmodrome involving a wrecked maintenance cabin has indefinitely delayed Russia's ability to launch crewed missions and payloads to the International Space Station (ISS).

Hot exozodiacal dust can thwart our efforts to detect exoplanets. It causes what's called coronagraphic leakage, which confuses the light signals from distant stars. The Habitable Worlds Observatory will face this obstacle, and new research sheds light on the problem.

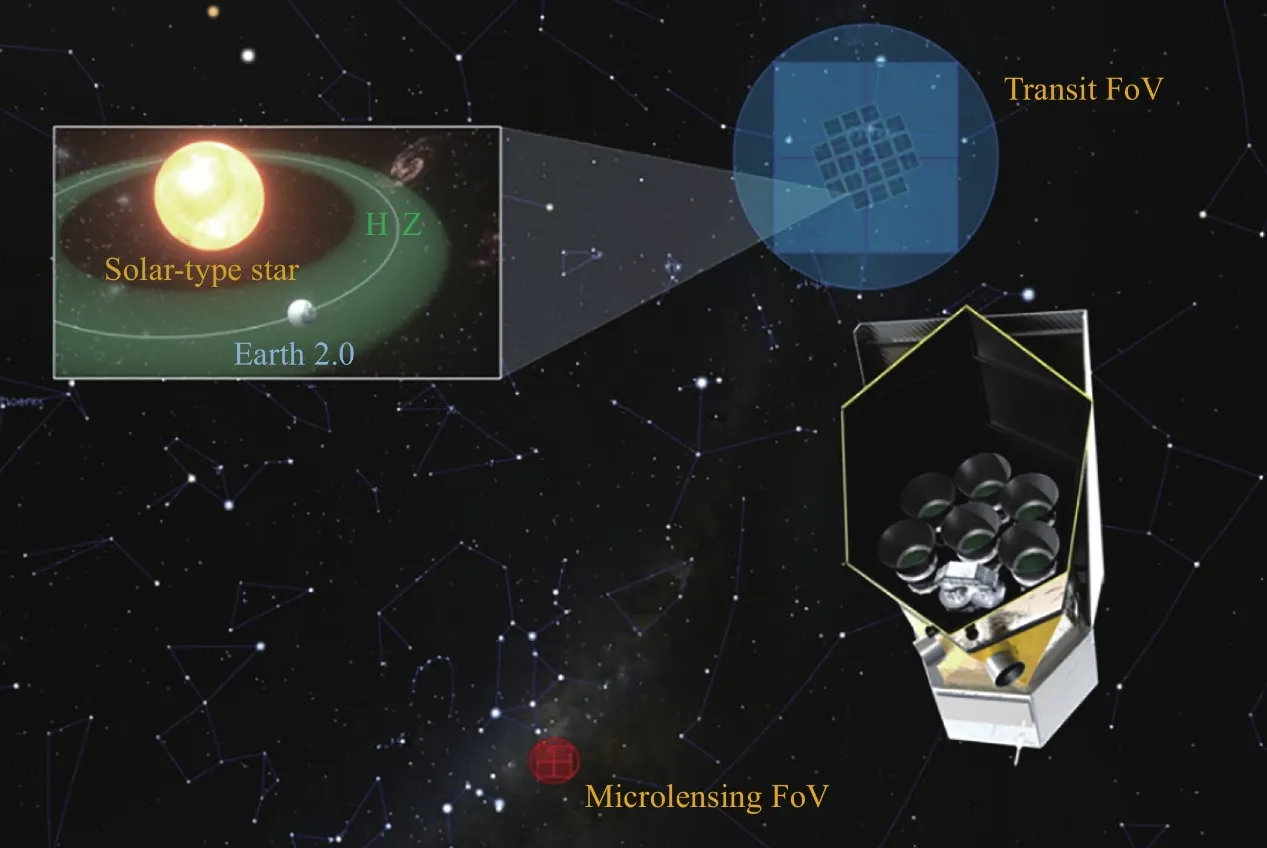

A video that appeared on CGTN's Hot Take details four missions that China will be sending to space in the coming years, including a survey telescope that will search for Earth 2.0.

A powerful geomagnetic superstorm is a once a generation event, happening once every 20-25 years. Such an event transpired on the night of May 10/11, 2024, when an intense solar storm slammed into the Earth’s protective magnetic sheath. Now, a recent study shows just how intrusive that storm was, and how long it took for the Earth’s plasma layer took to recover.

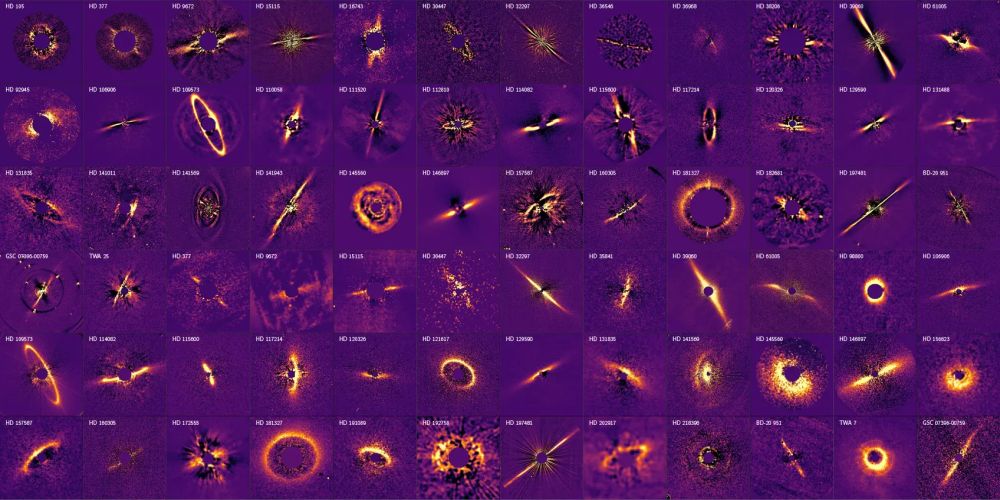

Observations with the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory's VLT revealed the presence of debris rings similar to structures in our Solar System. SPHERE found rings similar to the Kuiper Belt and the Main Asteroid Belt. Though individual asteroids and comets can't be imaged, these debris rings infer that other solar systems have architectures similar to ours.

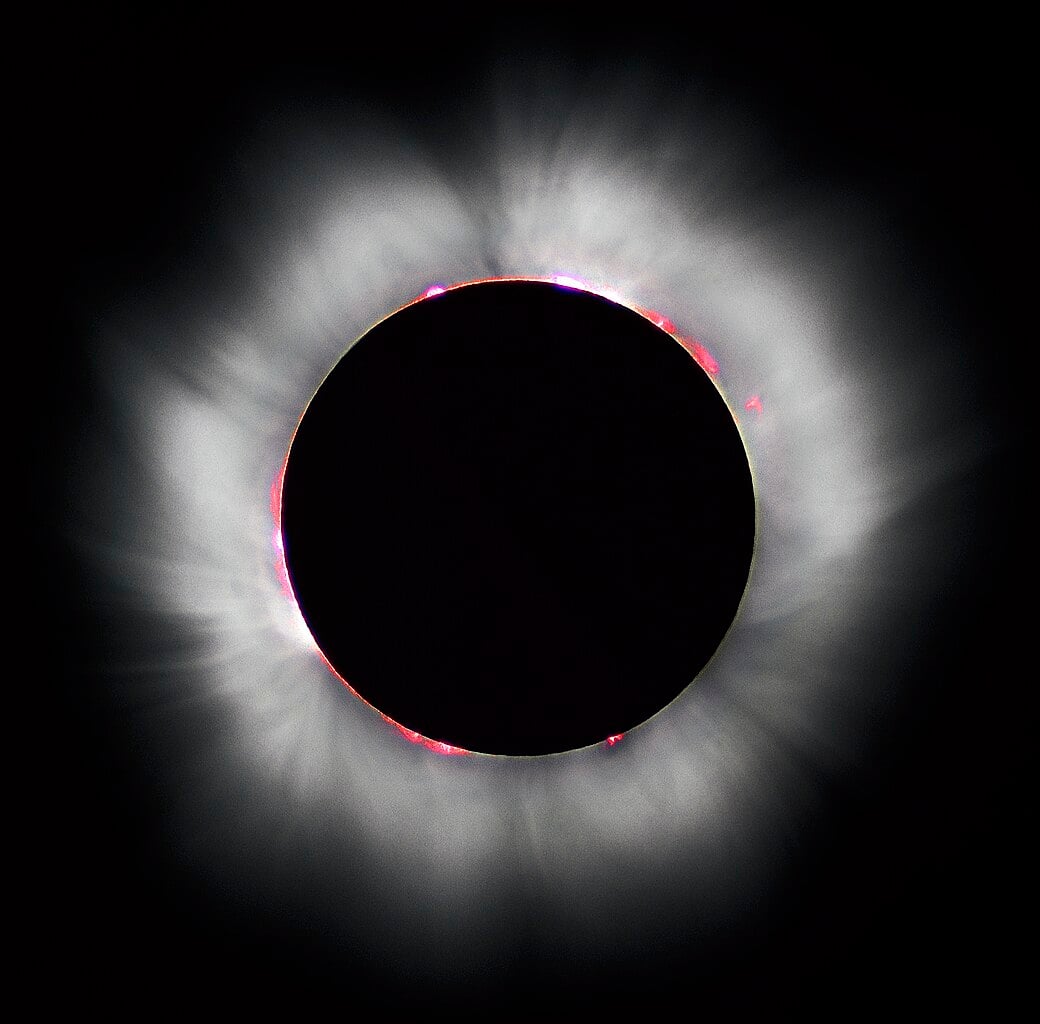

On a summer day in 709 BCE, scribes at the Lu Duchy Court in ancient China looked up to witness something extraordinary. The Sun vanished completely from the sky, and in its place hung a ghostly halo. They recorded the event carefully, noting that during totality the eclipsed Sun appeared "completely yellow above and below." Nearly three millennia later, that ancient observation has helped modern scientists measure how fast Earth was spinning and understand what our Sun was doing at a time when Homer was composing poetry.

An international team has made a significant breakthrough in understanding the tectonic evolution of terrestrial planets. Using advanced numerical models, the team systematically classified for the first time six distinct planetary tectonic regimes and identified a novel regime: the "episodic-squishy lid."